Floppy Disk Imaging

I want you to forget everything you know about about how floppy disks hold data. That's what I've had to do over the last few months as various projects I've been working on have challenged my understanding of them. I've completely changed my own workflows for working with floppy disk images as a result. This change in perspective has also made it much easier to adapt to new and completely unknown systems. Today I want to talk about how floppy disks store data at a lower level, how you can make more robust disk images, and how doing all that can give you some powerful abilities that can make things much easier and some wild things possible. You can use this knowledge for creating better copies of disks for preservation or for using disk images made by others with your own machines. So no matter what you are doing with them, this should help you better understand floppies.

Disk Formats are Variable

Why do you need a deeper understanding of imaging floppies, we've been doing this for decades, how hard can it be? Well, let's start with something more familiar, the 1.44MB 3.5in floppy disk for PCs. Although, that's not quite true, some of my disks say they hold 2MB instead, and this disk from Microsoft actually holds 1.6MB of data. This is a difference in formatting of the disks which defines how much data they can hold in practice. The 2MB quoted on the one disk is the raw unformatted capacity that you can't truly achieve due to many factors. The common 1.44MB format is the sum of 80 tracks over 2 sides with 18 blocks that hold 512 bytes each.

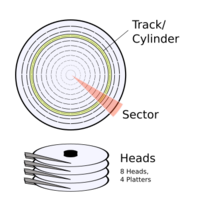

This is known as CHS addressing, standing for Cylinders, Heads, and Sectors. The radial surface of the disk is broken up into individual segments that each hold a portion of the data. On floppy disks we usually call cylinders tracks but this is how all floppy disks work at a fundamental level. The number of tracks, sides, sectors, and bytes per sector are the format. Only the number of tracks and sides are really linked directly to the hardware, sectors and how many bytes they hold are determined by the machine controlling the floppy drive. Different machines can define different formats that are incompatible.

Dealing with different formats is the bulk of the difficultly in working with floppy disks in a preservation setting. The hardware is not all that difficult to get or expensive. For the vast majority of disks you can get away with three drive types, a 40 track double sided 5.25in drive, 80 track double sided 5.25in drive, and an 80 track double sided 3.5in drive. 8in disks also work the same way as the smaller drives if you are working with those. You can get away with only an 80 track 5.25in drive most of the time for reading, but you shouldn't use it for writing 40 track disks because the head is narrower. I'll also mention that there isn't really a way to tell how many tracks a disk has without reading it first or just making an educated guess. There are also exotic disks readable only in the drives they were designed for like the 3in CFD or Zip disks, those will not be covered in this video. "Standard" floppy disk drives are all derived from a design by Shugart for their 8in floppy drives that was adopted by other manufactures for compatibility. We thankfully didn't have competing drive interfaces for too long because of this. This means using most drives is relatively simple. Typically this has been done by connecting drives to an older PC with a native floppy interface, but this isn't necessary anymore thanks to several different projects.

Reading Disks From Modern Computers

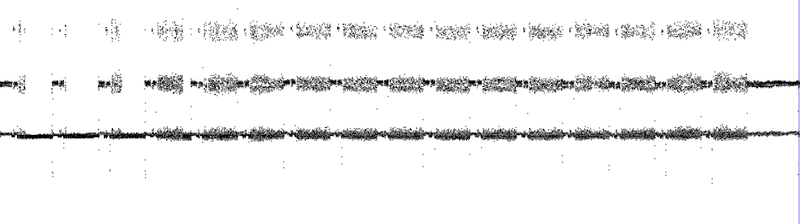

The two major devices I will be covering here are the KryoFlux and the Greaseweazle. I'll tell you right now that I will recommend the Greaseweazle above all other options because it is fully featured at a very low cost. For the moment I'm going to show using the Kryoflux though. These devices allow you to connect floppy drives to a modern system over USB. They don't make it "easy" to use the drives though, so don't expect to put in a disk and simply copy files off of it. The different potential formats make that mostly infeasible. Instead they provide a low level hardware interface to the drives and the software that controls them is designed primarily for doing full disk reads and a writes. The only thing you need to know beforehand is how many tracks you are working with and once you have that set you can start copying a disk. These devices are not tied to supporting any one specific format of disk, they can arbitrarily read any data on them as flux transitions. This why they are so powerful compared to using an old PC. This is as close as to raw analog data as you are going to get and this is how you should always read disks using these devices. The flux stream data can later be converted into anything else you need. The flux data can also be written back to a disk to make a direct copy without knowing how the disk was formatted. But that is an imperfect solution because you combine the minor calibration differences of each drive used to read and write the disks writing an ever more slightly out of spec format. Now Flux data is the backbone of a better workflow for preserving floppy disks and is the first step in how I read ever disk I back up now. What you do with the flux data after is where my view of floppies got turned upside down. But don't worry because it's really not that hard thanks to one more amazing tool.

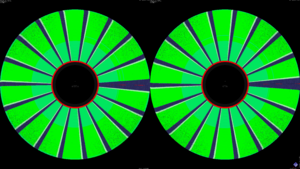

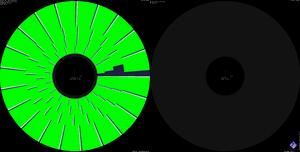

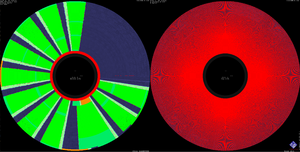

Once you have stream files the best way to work with and understand them is the HxC Floppy Emulator software. If you've ever seen a green data map of a floppy disk, this is how that was made. But this lets you see a lot more than a cool layout of the data on the disk, this can be a very helpful step in understanding the format of the disk. Here we can directly see the layout of the 18 sectors on both sides of the disk. You can also hover over each individual sector to see details about it like the sector ID, side, and track. These are stored in a header portion of the sector and are actually part of the metadata on the disk. A note about this disk layout view, there are different visualization options for it for representing different disk types, but you can always use "dummy disk" instead which works with all disks unlike the specific ones. There is more you can do with this software like switching into track view, zooming in, and seeing it decode the data, but there are a few more things we should go over now that you have a familiarity with the tools we will be using.

Disk Encoding

So far we have been working with flux data, but that isn't compatible with most software outside of what is specifically designed for preservation. So you will need to decode the flux data into binary data. This requires knowing not only the format of the disk, but also the encoding. The encoding is how the flux transitions on the disk translate into the binary 0s and 1s and also the timing of how the disk is read. You don't need to understand how the encoding works at a low level unless you are writing a flux converter yourself, but you do need to understand that there are three main encoding methods used by the majority of disks. FM, GCR, and MFM. Each of these are incompatible with each other due to how they encode the data but all existed for various reasons. You can tell which of these you are working with in HxC by looking at the sector information, but you can also make some rough guesses. 70s disks are more likely to be FM and were commonly called "Single Density". The Commodore 64, Apple II, and early Macs used GCR to fit a little more data than FM. But MFM commonly called "Double Density" and "High Density" came out shortly after that and all later disks used it instead. These aren't guarantees though, this Macintosh program (Specter published by Memorex) was actually shipped on an a disk with FAT12 MFM formatting like a PC. And some systems also used "density" to refer to different "tracks per inch" on drives. So a good step in your decoding process is to open your flux data in HxC to see how it is encoded before attempting to decode it. In the lower right there are different options for choosing what encoding method to view the flux data with. That's enough info to cover most disks you'll encounter but there are some edge cases we'll get back to after covering a few more things.

disk hd35

cyls = 80

heads = 2

tracks * ibm.mfm

secs = 18

bps = 512

end

|

Once you know the correct encoding for a disk you can start to work on converting the flux data into binary data. For common systems and disk formats this will be easy. HxC even had the ability to browse the files stored in some common disk formats. But when you start getting off the beaten path, you need to understand how to define your own formats. This is where I'm going to switch over the the Greaseweazle. You can do this with the Kryoflux, but the workflow for the gw software on the command line makes this easier for a few reasons. Formats can be loaded from text files that you can easily share and are known as disk definitions. gw ships with a large amount of diskdefs you can look at as examples. I want to start here by making a custom diskdef for the standard 1.44MB disk by looking at the flux data in HxC. The first two easy things are the tracks and sides, we can see the disk goes from track 0 to track 79, so we can set cylinders to 80, there are also obviously two sides of the same data. Next we are going to tell it to decode all tracks as MFM, all PC disks are MFM so this would be a safe guess but we can also verify that in HxC. Next is another easy one, we can count how many sectors there are to fill that in. Next is the bytes per sector, that is listed as the size in HxC, it's always a power of two so it can be pretty easy to guess as well. And that is all we need to convert this format. If we use this as the format and convert the flux to binary data we will get a perfectly standard IMG file! I can even mount this file in a virtual machine to open it and see the contents! This is the end of the basic process of preserving floppy disks using much better methods. I've now shown you all of the major steps and tools for working with any disk. But this example was easy, there are some true nightmares lurking that we have yet to cover. But lets not get to far ahead of ourselves and take a look at that 1.6MB floppy I showed at the start.

Understanding Non-Standard Disks

disk dmf35

cyls = 80

heads = 2

tracks * ibm.mfm

secs = 21

bps = 512

interleave = 2

end

|

This is a "DMF" formatted disk, a nonstandard larger capacity format by Microsoft to ship fewer disks for their larger products. It's mostly the same as the 1.4MB disk, but instead of 18 sectors it has 21 fit into the same space, a difference of about 16%. That may not sound like much, but if you go watch my video on installing Office 97 from 46 disks and imagine needing 8 more disks on top of that without DMF, I think you can see the benefits. There is more too this though than just having three more sectors. If we take a look at the flux we can see that the sector IDs aren't all in order. These disks use a concept called interleaving. This spaces out the sectors with sequential data giving the CPU time to work on what it has already received. If the system hasn't finished processing the data from one sector by the time it reaches the next it will ignore it and then wait for an entire disk rotation before attempting to read it again. Interleaving adds a built in delay, which for something like a compressed software install such as this, probably helps quite a bit to speed it up if the system is slower but doesn't delay it much for faster machines. When it comes to imaging though, this presents a bit of a problem, if we just changed the 18 to a 21 in out diskdef the sectors would be out of order in our binary image. So we have to specify the interleave in the diskdef so the software knows what order the data should be in.

This concept was used on many different machines, another example is my HP Series 200 setup. I have three different kinds of floppy drives for this computer. Each of them uses a different format and have different interleaves. The HP software even lets you custom define interleaves because some of the disks are interchangeable with other drives that might be even slower. However, some of these drives hold the exact same amount of data and use the same filesystem type known as LIF. Using the knowledge of what we learned so far, it's actually possible to image one disk as flux, convert it to binary data, and then rewrite it to a completely different kind of disk and format to use in a different drive! Looking at the flux maps of the two disks we can determine some basic diskdefs, the biggest different is the 3.5in disk only using one side. But a closer look will also reveal our fist unusual sector IDs that begin at 0 instead of 1. You specify that in the track area to handle it correctly. With the formats though, you can freely convert between disk types, I will say this is a slightly unique situation for the HP hardware because it uses an abstracted interface to the drives.

| HP LIF 5.25in Double Density/Double Sided | HP LIF 3.5in Double Density/Single Sided |

|---|---|

disk hp.lif.35dd

cyls = 35

heads = 2

tracks * ibm.mfm

id = 0

interleave = 1

secs = 16

bps = 256

end

end

|

disk hp.lif.70ss

cyls = 70

heads = 1

tracks * ibm.mfm

interleave = 2

secs = 16

bps = 256

end

end

|

disk kaypro.iv

cyls = 40

heads = 2

tracks 0-39.0 ibm.mfm

id=0

secs = 10

bps = 512

interleave = 5

end

tracks 0-39.1 ibm.mfm

id=10

h = 0

secs = 10

bps = 512

interleave = 5

end

end

|

In a recent video I worked on getting a Kaypro IV, that is roman numeral IV '83, working which was an evolution of the earlier Kaypro II. These are CP/M computers which there are great tools for working with binary disk images for that allow you to extract and put files onto the machines much easier. But you need to know what the formats are and how to convert them. Due to how CP/M works, the cpmtools also needs to know the disk format to skip past the BIOS that is stored on the first few sectors of the disk before the filesystem. Back to the Kaypro IV though, it represents an example of how coming at disk imaging from flux and inspection is needed. The disks for this machine are not standards complaint, the second side of the disk has the ID for the first side set and the sector numbers are sequential from the first side as well. Normally drives will read both sides of the disk without moving the head for faster data access. This machine though will read one whole side of the disk, and then the other, it's more like an automatic flip instead of being truly double sided. I don't have one to confirm, but I suspect this was done to make the Kaypro IV compatible with the Kaypro II's single sided disks since it would just stop reading anything after the "first half" of the disk. Back to imaging though, it is still possible to create a diskdef for this very unusual format. You can split your track decoding between sides, then make the second side start at sector 10 like we had set it to 0 for the HP disks. Then we have to set h=0 which tells software we are looking for side 1 headers, without this the software won't think the data isn't correct and suppose to be there. Then with everything else set correct you can convert the flux data using the new format and successfully validate the binary data using cpmtools to extract files.

disk trs80.sd-dd

cyls = 40

heads = 2

tracks 0 ibm.fm

id = 0

secs = 10

interleave = 2

bps = 256

end

tracks 1-39 ibm.mfm

id = 0

secs = 18

bps = 256

interleave = 4

end

end

|

Here's another example of a weird disk due to backwards compatibility, a TRS-80 Model 1 boot disk. This computer shipped with a floppy controller capable of using FM Single Density encoding. But it was extremely common and easy to upgrade this to MFM Double density using something like this Percom Disk Doubler. However, the machine could still only initiate booting from a FM disk. This was worked around though but having only the first track of the disk be FM, and then having the rest of the tracks be MFM to fit more data (DOS-PLUS). This is not the only system to do this either, here is an 8in CP/M-86 boot disk with the same mixed density track encoding in a different way. You can work with disk formats like this by specifying different track regions of the disk to be interpreted differently, like we did with the sides for the Kaypro. For the TRS-80 we can create a diskdef with track 0 as FM with 10 sectors of data and an interleave of 2. Then we specify the tracks of 1-39 as MFM with 18 sectors and an interleave of 4. And both sections have 256 bps, they are just sized differently because of the encoding. And with that, we can convert flux data into a binary image yet again for another strange disk type!

Completely Custom Disk Types

Now lets take this different track types concept in another direction by looking at some Mac and C64 disks. These use GCR encoding because they came out before MFM was common and were trying to fit more data than FM. However, the real unique thing about them is that they both use Zone Bit Recording which is not related to GCR. The bit rate of the drive relative to the disk material changes based on the distance from the center of the disk. Each system did this differently, Apple changed the speed of the motor spinning the disk and Commodore changed the clock rate the head syncs to. This allowed more efficient usage of space on a disk compared to fixed speed recording, if the inner part of the disk is capable of holding the same amount of data in half the space, why not double it on the outer tracks? The actual reason to not use ZBR is the complexity it adds to the drives massively increasing cost relative to "dumb" fixed bitrate drives and both companies switched to or at least supported MFM later. Now when it comes to decoding the format of these disks it isn't all that different from the FM and MFM mixed density disks we just looked at. The main difference is that you have to change the clock rate as you move from the outside in. However, there isn't as much of a need to make a custom definition here, the Macs and Commodore systems that used these formats are so popular they have already been added to the main Greaseweazle diskdef file and you should use those. In the unlikely event you encounter Zone Bit Recording on something else though, you know it is possible and that there are examples though.

I want to end this with another example that I wouldn't exactly recommend trying to decode yourself. This is Microsoft Adventure for the IBM PC. This is the first game for the PC, and it has DRM. More specifically it has copy protection. The PCs originally shipped with disks formatted with 8 MFM sectors on a single single side. Microsoft Adventure though....uh...didn't. It was entirely possible to manually control the floppy drive on a PC to make custom and strange formats that only your program was designed to work with. This game is booted onto the system to run, not loaded form DOS, so it has full hardware access. This wasn't the only game like this, here's Sublogic's Jet that has a normal first track and then a weird 5 sector format after. You could define diskdefs for these disks, but this is a harder subject that also gets into defeating the checks built into the game's executables as well which is beyond the scope of this video. For disks like this, I would recommend sticking with just flux for preservation unless you really want a challenge.

And that is finally everything I think you should know to get started with working with floppy disks at a low level for preservation purposes. When you are making archival copies of disks you should always keep and backup flux data as well because it could be used in different ways later. But it isn't the best for making new disks and working with other tools, so knowing how decoding works is very important as well. The way I work with disks now is to read flux data, use HxC to generate an image of the flux map, check it for the structure, and then use a dedicated script to both decode the flux to binary data and attempt to validate my final image by using other tools to extract files to test it in some way. It's been very easy to build up a robust and powerful set of tools using these amazing projects. I hope I've given you all of the information you need to do that as well.